Simple Food Change Could Help Prevent Crohn’s Disease

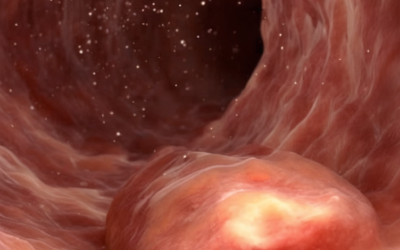

If you’re living with Crohn’s disease or caring for someone who is, you know how desperately we all wish there had been some way to prevent this condition from ever taking hold. The unpredictable flares, the emergency bathroom runs, the careful meal planning around trigger foods—it’s a life-changing diagnosis that reshapes everything from career choices to weekend plans.

While we can’t turn back time for those of us already living with IBD, new research offers hope for the next generation. What if something as simple as adding more of certain foods to our plates could help protect our loved ones from developing Crohn’s disease in the first place?

Summary of Medscape article

A major new study followed over 220,000 women for 25 years, tracking their eating habits and health outcomes. The researchers discovered that women who ate more fermentable fiber—found in foods like beans, oats, bananas, and certain vegetables—were significantly less likely to develop Crohn’s disease.

What makes fermentable fiber special? Unlike regular fiber that just helps with digestion, this type of fiber gets broken down by the good bacteria in your gut. When this happens, it creates substances called short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that help keep your gut lining healthy, reduce inflammation, and maintain a balanced microbiome—all things that may protect against Crohn’s disease.

Interestingly, this protective effect was specific to Crohn’s disease. The study didn’t find the same benefit for ulcerative colitis, suggesting these two types of IBD may respond differently to dietary factors.

This post summarizes reporting from Medscape article. Our analysis represents IBD Movement’s perspective and is intended to help patients understand how this news may affect them. Read the original article for complete details.

What This Means for the IBD Community

This research hits close to home for so many of us in the IBD community. As parents, siblings, or partners of people with Crohn’s, we’ve all wondered about the genetic component. We know that having a family member with IBD increases risk, and that uncertainty can weigh heavily on our minds. Will my children develop this? Could my spouse be at higher risk because of stress from caring for me?

While genetics play a role, this study reinforces something many of us have suspected: our gut health and what we feed our microbiome matters enormously. The fact that fermentable fiber specifically showed protection against Crohn’s—but not ulcerative colitis—tells us that these two conditions, while both classified as IBD, may have different underlying mechanisms and risk factors.

For families dealing with IBD, this research opens up important conversations about prevention strategies. It’s empowering to know that something as accessible as increasing certain foods in our family’s diet could potentially make a difference. We’re not talking about expensive supplements or complicated elimination diets—we’re talking about beans, oats, and bananas.

However, it’s crucial to understand the limitations here. This was an observational study, meaning it shows association, not causation. We can’t definitively say that eating more fermentable fiber prevents Crohn’s disease—we can say that people who ate more of these foods were less likely to develop it. There could be other factors at play that the researchers couldn’t account for.

Additionally, this study focused on prevention in healthy individuals, not management of existing IBD. For those of us already living with Crohn’s or UC, increasing fiber can be complicated. Many of us have learned through painful experience that high-fiber foods can trigger flares, especially during active inflammation. The same foods that might help prevent IBD could potentially worsen symptoms in someone who already has the condition.

This creates a complex situation for IBD families. Parents with IBD might want to increase fermentable fiber in their children’s diets for potential protection, while carefully managing their own fiber intake to avoid triggering symptoms. It’s a delicate balance that requires individual consideration and medical guidance.

The timing of fiber introduction might also matter. The protective effects observed in this study likely developed over years or decades of consistent intake. This suggests that building healthy gut bacteria through fermentable fiber is a long-term investment, not a quick fix.

Questions to Discuss with Your Healthcare Team

This research raises several important questions worth discussing with your doctors:

- For parents with IBD: How can we safely increase fermentable fiber in our children’s diets while managing our own condition?

- What’s the optimal amount and type of fermentable fiber for potential IBD prevention?

- Should family members of people with IBD consider specific dietary changes based on this research?

- For those with IBD in remission: Could gradually increasing fermentable fiber be beneficial, or does it carry too much risk of triggering flares?

- How does this research fit with other IBD prevention strategies we should be considering?

Your gastroenterologist and a registered dietitian familiar with IBD can help you navigate these questions based on your individual family history, current health status, and personal circumstances.

The Bigger Picture: Hope for IBD Prevention

This study is part of a larger shift in IBD research toward understanding prevention rather than just treatment. For too long, IBD has been viewed as an inevitable consequence of genetic predisposition combined with unknown environmental triggers. But research like this suggests we might have more control over our IBD risk than previously thought.

The focus on fermentable fiber and the gut microbiome also aligns with growing evidence that our gut bacteria play a crucial role in immune system development and regulation. When we feed our beneficial bacteria with fermentable fiber, we’re essentially training our immune system to maintain better balance and avoid the kind of chronic inflammation that characterizes IBD.

This doesn’t mean we should view IBD as a lifestyle disease or blame ourselves for developing it. The reality is that IBD results from a complex interaction of genetics, environment, immune system function, and likely factors we don’t even understand yet. But it does mean that for future generations, we might have evidence-based tools to help reduce risk.

The specificity to Crohn’s disease is particularly intriguing and reinforces what many researchers suspect: that Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis, while both IBDs, may be quite different diseases with different triggers and risk factors. This could lead to more targeted prevention strategies in the future.

For our community, this research represents hope. Hope that our children and grandchildren might have a lower risk of experiencing what we’ve been through. Hope that simple, accessible dietary changes could make a real difference. And hope that continued research will give us even better tools for prevention and management.

While we wait for more definitive research, incorporating fermentable fiber-rich foods into our families’ diets—when appropriate and safe to do so—seems like a reasonable, low-risk strategy. Foods like oats, bananas, beans, and certain vegetables aren’t just potentially protective against IBD; they’re also associated with better overall health outcomes.

This research doesn’t solve the IBD puzzle, but it does give us another piece of it. And for a community that has learned to find hope in small victories and incremental progress, that piece matters enormously. It reminds us that while we can’t control everything about IBD, we might have more influence over our family’s risk than we previously realized.

IBD Movement provides information for educational purposes only. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.