Hidden Gut Infections May Secretly Trigger Your Next IBD Flare

Have you ever wondered why your IBD symptoms suddenly flare up seemingly out of nowhere? One day you’re managing well, and the next, you’re dealing with intense abdominal pain, urgency, and all the familiar struggles that come with a flare. It’s one of the most frustrating aspects of living with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis—the unpredictability that keeps us constantly on edge.

What if I told you that researchers have identified a hidden culprit that might be secretly triggering some of these unexpected flares? New research is revealing how common bacterial infections in our gut—infections we might not even realize we have—could be setting off the inflammatory cascade that leads to IBD flares.

Summary of Medscape

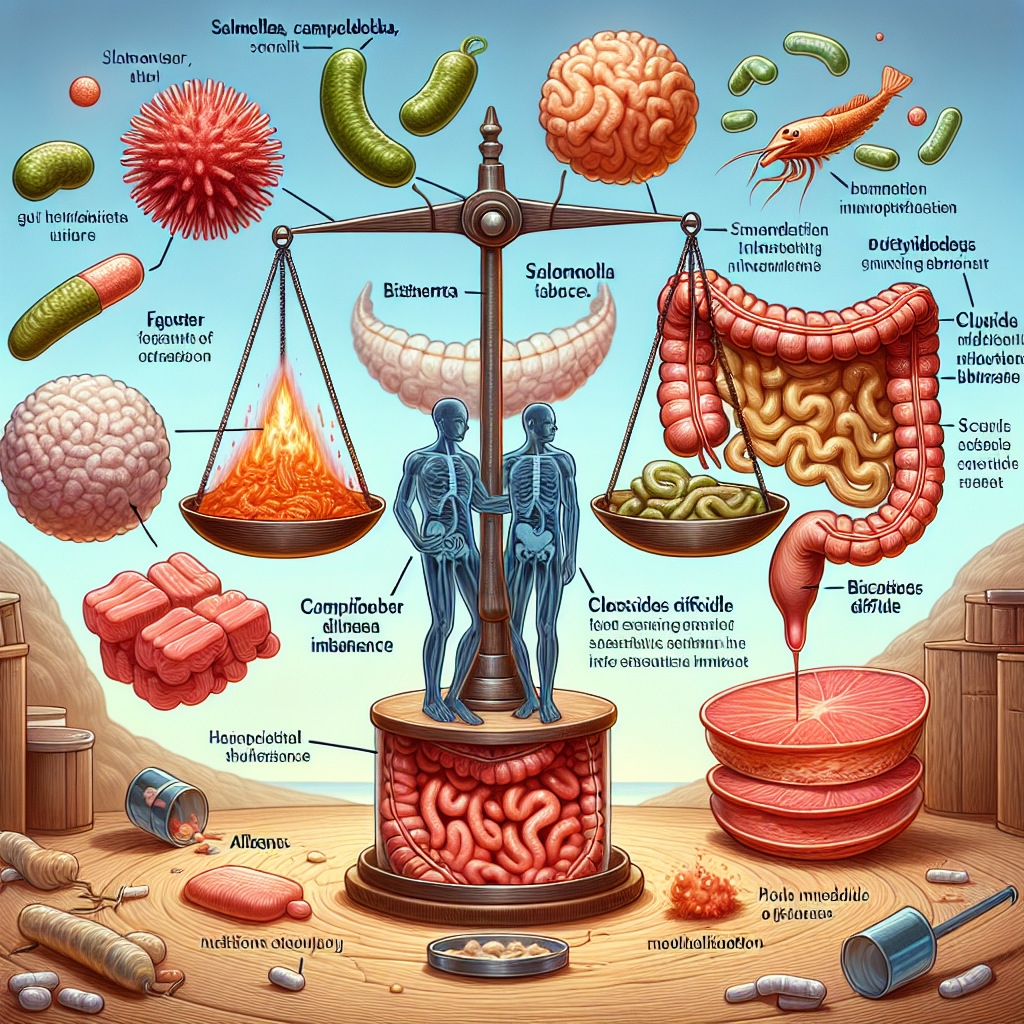

A groundbreaking study examined over 600,000 IBD patients in Denmark to understand the connection between bacterial gut infections and IBD flares. Researchers tracked patients who experienced common bacterial infections like Salmonella, Campylobacter, and C. difficile to see if these infections correlated with subsequent flare-ups.

The results were significant: patients who had documented bacterial gut infections faced double the risk of experiencing an IBD flare within six months. The elevated risk wasn’t just temporary—it persisted for up to a year after the infection. During this period, patients were also more likely to need corticosteroids, require hospitalization, or even undergo surgery.

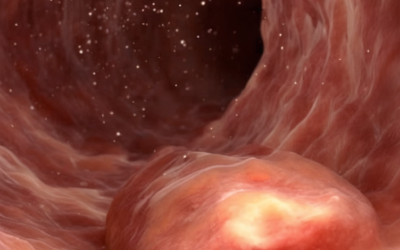

The study suggests that these infections disrupt the delicate balance of our gut microbiome, triggering an aggressive immune response that can push vulnerable IBD patients into a full-blown flare. C. difficile infections appeared particularly problematic for people with ulcerative colitis, showing dramatically increased risks of severe outcomes.

This post summarizes reporting from Medscape. Our analysis represents IBD Movement’s perspective and is intended to help patients understand how this news may affect them. Read the original article for complete details.

What This Means for the IBD Community

This research validates what many of us have suspected for years—that there are identifiable triggers for our flares, even when they seem to come out of nowhere. As someone who’s connected with thousands of IBD patients over the years, I’ve heard countless stories of people saying, “I had what I thought was just a stomach bug, and then everything went downhill from there.” This study gives scientific backing to those experiences.

What’s particularly striking about these findings is how they reframe our understanding of “random” flares. Many of us have felt frustrated when our gastroenterologists ask, “What do you think triggered this flare?” and we genuinely don’t know. Now we’re learning that some triggers might be microscopic invaders we never even realized were there.

The year-long elevated risk period is especially important for our community to understand. This means that even after you’ve recovered from what seemed like a minor bout of food poisoning or a stomach bug, your IBD might remain more vulnerable for months. This knowledge could be incredibly empowering for both patients and healthcare providers in managing care proactively.

For those of us with ulcerative colitis, the heightened risk associated with C. difficile infections is particularly concerning. C. diff is already a serious infection that can be challenging to treat, and knowing it poses extra risks for UC patients underscores the importance of prevention and early intervention.

From a practical standpoint, this research might explain some of the patterns we’ve noticed in our own disease management. Have you ever had a period where you seemed to have one flare after another? It’s possible that an initial bacterial infection set off a cascade that made your gut more susceptible to subsequent problems.

This information also has implications for how we think about travel, dining out, and food safety. While we shouldn’t live in fear, understanding that foodborne infections pose additional risks for our IBD management can help us make more informed decisions about when to be extra cautious.

The research opens up new possibilities for preventive care strategies. Instead of only focusing on maintenance medications and lifestyle factors, our healthcare teams might now consider more aggressive monitoring and intervention after any suspected or confirmed bacterial gut infection. This could include closer follow-up appointments, earlier intervention with anti-inflammatory treatments, or even prophylactic measures to prevent flares.

I’m also thinking about how this affects our self-advocacy as patients. When we’re seeing our gastroenterologists, we might want to be more proactive about reporting any episodes of gastroenteritis, food poisoning, or unusual digestive symptoms—even if they seemed minor at the time. These details could be crucial for our doctors in predicting and preventing future flares.

For caregivers and family members, this research highlights the importance of taking any stomach bug or digestive upset seriously in their loved ones with IBD. What might be a minor inconvenience for someone without IBD could potentially trigger months of complications for us.

The study also raises important questions about antibiotic use in IBD patients. While antibiotics are sometimes necessary to treat bacterial infections, they can also disrupt our gut microbiome in ways that might increase flare risk. This creates a complex balancing act that our healthcare providers will need to navigate carefully.

Looking forward, this research might influence how clinical trials are designed for IBD treatments. If bacterial infections are a significant trigger for flares, researchers might need to account for these factors when measuring the effectiveness of new therapies.

Questions to Discuss with Your Doctor

This research raises several important questions you might want to bring up at your next appointment:

- Should you be monitored more closely after any episode of gastroenteritis or suspected food poisoning?

- Are there specific preventive measures you should take when traveling or in situations with higher infection risk?

- How should bacterial infections be treated differently in IBD patients?

- Should your maintenance therapy be adjusted during or after a bacterial infection?

- What early warning signs should you watch for that might indicate an infection-triggered flare?

Understanding these connections between infections and flares represents a significant step forward in personalized IBD care. It moves us away from the frustrating “we don’t know why you’re flaring” conversations toward more targeted, proactive management strategies.

While we can’t eliminate all bacterial infections from our lives, knowing about this connection gives us more tools to protect ourselves and work with our healthcare teams to minimize the impact when infections do occur. It’s another piece of the complex IBD puzzle that brings us closer to better, more predictable disease management.

This research also underscores the importance of maintaining good gut health through probiotics, a balanced diet, and other microbiome-supporting practices. While these measures won’t prevent all infections, they might help our guts recover more quickly and resist the inflammatory cascade that leads to flares.

The validation this study provides is profound. For too long, many of us have felt like our flares were random, uncontrollable events. Learning that there are identifiable, scientifically-backed triggers helps remove some of the mystery and self-blame that often accompany IBD management. It’s not that we did something wrong or failed to take care of ourselves—sometimes, we’re dealing with microscopic challenges that are largely beyond our immediate control.

Most importantly, this research opens the door for better predictive care and intervention strategies. Instead of only reacting to flares after they’ve started, we might soon be able to take preventive action based on early signs of bacterial infections. This shift from reactive to proactive care could significantly improve quality of life for millions of people living with IBD.

The study’s large scale—over 600,000 patients—gives us confidence in these findings. This isn’t a small pilot study with questionable applicability; it’s robust evidence that should influence how IBD care is approached going forward.

For our community, this research represents hope. Hope that we’re moving toward more personalized, predictable care. Hope that the seemingly random nature of our flares might become more manageable. And hope that by understanding our triggers better, we can take more control over our IBD journey.

As we continue to learn more about these connections, I encourage everyone to stay engaged with the latest research and maintain open communication with their healthcare teams. Every new discovery brings us closer to better treatments, better outcomes, and ultimately, better lives with IBD.

IBD Movement provides information for educational purposes only. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.