The Hidden Symptoms Your Gastroenterologist Might Miss: Why IBD Care Must Look Beyond the Gut

When Sarah first noticed the red, painful bump on her shin, she dismissed it as a minor injury. When her vision became blurry and her eye started hurting, she blamed too much screen time. It wasn’t until her joints began aching that she mentioned these seemingly unrelated symptoms to her gastroenterologist during a routine Crohn’s disease follow-up. What she discovered changed everything: her IBD wasn’t just affecting her intestines—it was launching a systematic attack on her entire body.

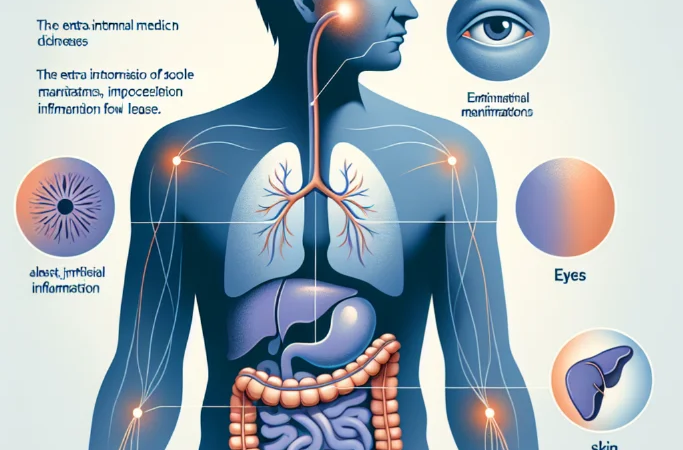

Sarah’s story illustrates a critical gap in IBD care that affects up to 50% of people living with inflammatory bowel disease. Extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) of IBD—symptoms that occur outside the digestive tract—are not rare complications but common, often debilitating extensions of the disease that demand immediate attention and coordinated care. Yet too many patients suffer in silence, attributing eye pain to fatigue, joint aches to aging, or skin lesions to unrelated conditions, while their IBD quietly wages war beyond their gut.

The time has come for a fundamental shift in how we approach IBD care. We must move beyond the narrow focus on intestinal symptoms and embrace a holistic understanding that IBD is truly a systemic inflammatory disease requiring comprehensive, multi-specialty management.

The Current Reality: A Fragmented Approach to Whole-Body Disease

Today’s IBD care model reflects an outdated understanding of the disease. Most gastroenterologists excel at managing intestinal inflammation, adjusting medications, and monitoring for complications like strictures or perforations. However, when it comes to extraintestinal manifestations affecting the eyes, joints, skin, and liver, the system often fails patients.

Consider the numbers: approximately 25-40% of people with IBD will develop arthritis or joint pain, yet many gastroenterologists lack the training to distinguish IBD-related arthropathy from medication side effects or other rheumatologic conditions. Eye complications like uveitis and episcleritis affect 2-5% of IBD patients and can lead to permanent vision loss if not caught early, but routine ophthalmologic screening isn’t standard practice in most IBD clinics.

The consequences of this fragmented approach are severe. Patients bounce between specialists, each focusing on their organ system while missing the bigger picture. A dermatologist treats erythema nodosum without considering IBD activity. An ophthalmologist manages uveitis without coordinating with the gastroenterology team. Meanwhile, the patient struggles to understand how these seemingly separate conditions connect to their IBD, often feeling like their body is betraying them in multiple ways simultaneously.

This disconnect isn’t just inconvenient—it’s dangerous. EIMs can be the first sign of IBD flare-ups, sometimes appearing before intestinal symptoms. They can also indicate the need for more aggressive systemic therapy. When these manifestations go unrecognized or are treated in isolation, patients miss opportunities for better disease control and face increased risk of permanent complications.

A New Vision: IBD as a Systemic Inflammatory Disease

The evidence is overwhelming: IBD extraintestinal manifestations aren’t random complications—they’re predictable extensions of the same inflammatory processes affecting the gut. The shared pathways involve similar immune dysfunction, genetic predispositions, and inflammatory mediators. This understanding should fundamentally reshape how we approach IBD care.

Eye complications deserve particular attention because of their potential for irreversible damage. Uveitis, the most serious ocular manifestation, can cause permanent vision loss if not treated promptly. Yet many IBD patients have never been told to watch for eye symptoms or haven’t received baseline ophthalmologic evaluations. The red, painful eye that patients might dismiss as “pink eye” could be anterior uveitis requiring immediate steroid treatment.

Similarly, IBD-related arthritis affects quality of life as much as intestinal symptoms for many patients. Unlike rheumatoid arthritis, IBD arthropathy often doesn’t cause permanent joint damage, but it can be incredibly painful and debilitating. More importantly, joint symptoms often correlate with intestinal disease activity, serving as a valuable clinical marker that gastroenterologists should actively monitor and address.

Skin manifestations like erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum aren’t just cosmetic concerns—they’re windows into disease activity and treatment response. These lesions often appear during flares and may resolve with effective IBD treatment, but they can also persist independently, requiring targeted dermatologic intervention while maintaining systemic IBD therapy.

The liver complications, particularly primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), represent perhaps the most serious extraintestinal manifestation, significantly impacting long-term prognosis. Yet liver enzyme monitoring varies widely among IBD practices, and many patients aren’t educated about symptoms that might indicate hepatic involvement.

Addressing the Skeptics: Why Comprehensive Care Matters

Some argue that expecting gastroenterologists to manage extraintestinal manifestations creates unrealistic expectations and could compromise their expertise in intestinal disease management. They contend that the current referral-based system, while imperfect, allows each specialist to focus on their area of greatest competence.

This perspective, while understandable, misses the fundamental interconnectedness of IBD manifestations. The goal isn’t for gastroenterologists to become ophthalmologists or rheumatologists, but rather to recognize EIMs early, understand their relationship to intestinal disease activity, and coordinate care effectively with other specialists.

Critics also worry about healthcare costs and access issues, arguing that routine screening for extraintestinal manifestations might strain resources and create unnecessary anxiety for patients. However, the cost of missed or delayed diagnosis far exceeds the expense of proactive screening. A patient who develops irreversible vision loss from undiagnosed uveitis, or who requires multiple emergency department visits for unrecognized IBD arthritis, generates far greater healthcare costs than routine ophthalmologic screening and coordinated rheumatologic care.

Some patients themselves resist the idea that their IBD might affect other body systems, preferring to compartmentalize their health issues. This psychological defense mechanism is understandable—IBD already feels overwhelming without adding concerns about eyes, joints, and skin. However, education about EIMs empowers patients to seek appropriate care early, potentially preventing serious complications and improving overall outcomes.

What Must Change: A Blueprint for Comprehensive IBD Care

The solution requires systematic changes at multiple levels, starting with medical education. Gastroenterology training programs must incorporate comprehensive education about extraintestinal manifestations, including recognition, initial management, and coordination of care. Current fellows often graduate with limited knowledge about EIMs, perpetuating the fragmented care model.

IBD clinics should implement standardized screening protocols for extraintestinal manifestations. This includes baseline ophthalmologic examinations for all IBD patients, routine joint symptom assessments, skin examinations, and liver function monitoring. These screenings don’t require gastroenterologists to become experts in other specialties, but they do require systematic approaches to detection and referral.

Healthcare systems must facilitate better communication between specialists treating IBD patients. Electronic health records should flag IBD patients for all providers, and treatment decisions should be coordinated to ensure that therapies for extraintestinal manifestations don’t conflict with IBD management. A patient receiving local steroid injections for arthritis needs their gastroenterologist to know about potential systemic effects.

Patient education represents another critical component. IBD patients should receive comprehensive information about extraintestinal manifestations during diagnosis, not as afterthoughts when symptoms develop. Educational materials should include specific symptoms to watch for, when to seek urgent care, and how EIMs relate to overall disease management.

Insurance coverage policies must recognize the interconnected nature of IBD and its extraintestinal manifestations. Prior authorization requirements that treat EIMs as separate conditions from IBD create barriers to appropriate care and force patients to navigate bureaucratic obstacles while their symptoms worsen.

The Path Forward: Embracing Whole-Person IBD Care

The future of IBD care lies in recognizing that inflammatory bowel disease is exactly what its name suggests—a systemic inflammatory condition that happens to have prominent intestinal manifestations. This perspective shift opens possibilities for better patient outcomes, more efficient healthcare delivery, and improved quality of life for millions of people living with IBD.

Imagine an IBD care model where newly diagnosed patients receive comprehensive education about potential extraintestinal manifestations, baseline screening examinations, and clear instructions about when to seek help. Picture IBD clinics where gastroenterologists routinely ask about joint pain, eye symptoms, and skin changes, understanding these as potential markers of disease activity rather than unrelated complaints.

This vision isn’t utopian—it’s achievable with commitment from healthcare providers, patients, and healthcare systems. Some IBD centers already implement comprehensive care models with excellent results. The challenge is scaling these approaches and making them standard practice rather than exceptional care.

People with IBD deserve healthcare providers who see them as whole human beings, not just collections of symptoms confined to organ systems. They deserve coordinated care that recognizes the connections between their joint pain and their Crohn’s flare, their eye inflammation and their ulcerative colitis activity. Most importantly, they deserve the opportunity to prevent serious complications through early recognition and appropriate treatment of extraintestinal manifestations.

The time for fragmented IBD care is over. The evidence is clear, the tools are available, and the need is urgent. It’s time to embrace IBD as the systemic disease it truly is and provide the comprehensive, coordinated care our community deserves.