When IBD Affects Your Breathing: A Hidden Risk You Should Know

When you live with IBD, you become intimately familiar with the unpredictability of chronic illness. Just when you think you’ve mapped out all the ways your condition might surprise you, research reveals another connection that catches you off guard. For many of us in the IBD community, the idea that our gut condition could affect our lungs feels almost overwhelming—like we’re playing a game where the rules keep changing.

But here’s the thing about knowledge in chronic illness: even when it’s scary at first, it ultimately gives us power. A recent study has revealed something important about the connection between IBD and our respiratory health, and while it might add another item to our already long list of things to monitor, it also gives us the chance to be proactive about our care.

Summary of the original source

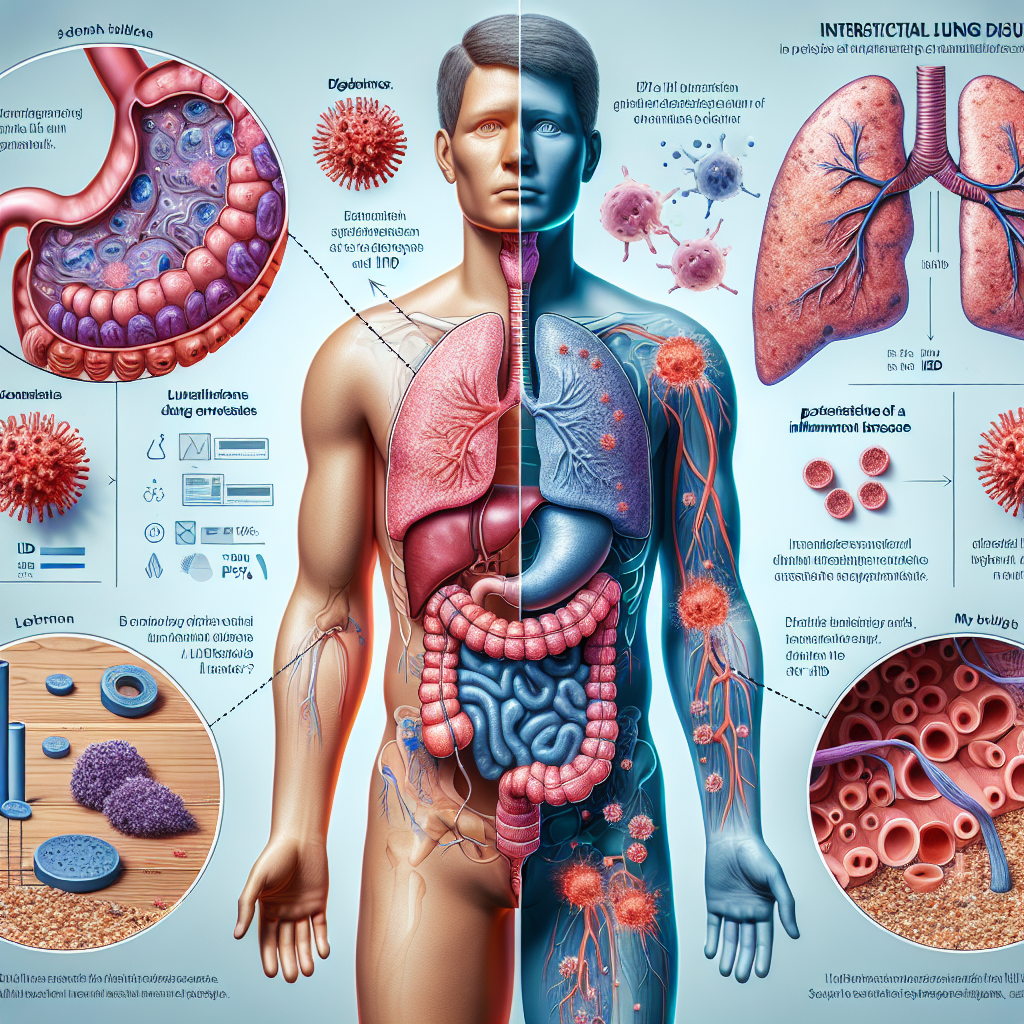

New research from Sweden has uncovered a significant link between inflammatory bowel disease and interstitial lung disease (ILD), a condition that causes scarring in the lungs and can lead to breathing difficulties. The large-scale study found that people with IBD are nearly 50% more likely to develop ILD compared to those without IBD.

This increased risk was consistent across all types of IBD—Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis alike. Importantly, researchers compared IBD patients not just to the general population, but also to their own siblings, which helps rule out shared genetic or environmental factors. The fact that the risk remained elevated even in these sibling comparisons suggests that IBD itself is driving this connection.

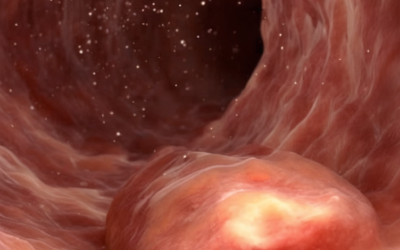

Interstitial lung disease involves inflammation and scarring of the tissue around the air sacs in the lungs, which can make breathing difficult and reduce the lungs’ ability to transfer oxygen to the bloodstream. Symptoms can include persistent cough, shortness of breath, and fatigue—symptoms that might be easily overlooked or attributed to other causes in people already managing a chronic condition.

This post summarizes reporting from the original source. Our analysis represents IBD Movement’s perspective and is intended to help patients understand how this news may affect them. Read the original article for complete details.

What This Means for the IBD Community

First, let’s address the elephant in the room: this news might feel overwhelming. If you’re like most people with IBD, you’re already juggling medication schedules, dietary considerations, regular monitoring, and the everyday unpredictability of your condition. The last thing you want to hear is that there’s another potential complication to worry about.

But here’s how I encourage you to think about this information: it’s not about adding fear to your life—it’s about adding awareness that could potentially save it. Many of us in the IBD community have learned that being informed advocates for our own health often makes the difference between catching problems early and dealing with them when they become more serious.

The connection between IBD and lung problems actually makes sense when you consider how inflammatory bowel disease works. IBD isn’t just about inflammation in your digestive tract—it’s a systemic inflammatory condition that can affect other parts of your body. We already know that IBD can involve complications like arthritis, skin conditions, and eye problems. The lungs, it turns out, are another potential target of this systemic inflammation.

What’s particularly important about this research is that it helps explain symptoms that many IBD patients might experience but not connect to their condition. Have you ever noticed that you feel more short of breath during a flare? Or developed a persistent cough that your doctor attributed to allergies or a lingering cold? While these symptoms have many possible causes, this research suggests that in some cases, they might be related to IBD’s effects beyond the gut.

This knowledge can change how we approach our healthcare conversations. Instead of compartmentalizing our IBD care from our overall health, we can encourage our medical teams to think more holistically. It’s a reminder that when you have a systemic inflammatory condition, no symptom exists in isolation.

From a practical standpoint, this research doesn’t mean you need to panic or assume you’ll develop lung problems. The increased risk is significant from a research perspective, but it’s important to remember that even a 50% increase in risk might still translate to a relatively small absolute risk for any individual patient. What it does mean is that you have valuable information to share with your healthcare team.

Consider discussing these findings with your gastroenterologist and primary care physician. Ask them about what respiratory symptoms you should watch for and whether any changes in your breathing patterns or exercise tolerance might warrant investigation. Some questions you might want to discuss include: What respiratory symptoms should prompt me to seek evaluation? How often should I have my lung function assessed? Are there any early screening tools that might be appropriate for IBD patients?

This research also highlights why comprehensive IBD care is so important. The best IBD specialists don’t just look at your gut—they consider how your condition affects your entire body and work with other specialists when needed. If you’re not already working with a gastroenterologist who takes this holistic approach, this might be a good time to seek one out or advocate for more comprehensive care.

For caregivers and family members, this information provides another reason to take note of changes in your loved one’s breathing or energy levels. Sometimes when you’re living with chronic illness, you become so accustomed to not feeling 100% that you might dismiss symptoms that actually warrant attention. Having extra eyes and ears watching for changes can be invaluable.

Looking at the Bigger Picture

This research fits into a growing understanding of IBD as a truly systemic condition. Over the past decade, we’ve seen increasing recognition that inflammatory bowel disease affects far more than just the digestive system. This lung connection joins a growing list of “extraintestinal manifestations” of IBD—complications that occur outside the gut but are directly related to the underlying inflammatory process.

What’s encouraging about this trend in research is that it’s leading to more comprehensive care approaches. Rather than treating IBD symptoms in isolation, medical teams are increasingly thinking about how to manage the systemic inflammation that drives the condition. This could lead to treatment strategies that not only improve gut symptoms but also reduce the risk of complications like interstitial lung disease.

The Swedish study’s methodology is particularly noteworthy because it compared IBD patients to their siblings, which helps control for genetic and environmental factors that families share. This strengthens the evidence that the connection between IBD and lung disease is real and directly related to the inflammatory bowel condition itself, not just to other factors that might run in families.

This kind of research also emphasizes why patient registries and large-scale studies are so valuable in understanding rare complications of chronic conditions. Individual doctors might see only a few cases of IBD patients developing lung problems, making it hard to recognize patterns. But when researchers can analyze data from thousands of patients, these important connections become clear.

Knowledge like this empowers both patients and healthcare providers to be more vigilant about potential complications while avoiding unnecessary anxiety about problems that remain relatively uncommon. It’s the difference between living in fear and living with informed awareness—a crucial distinction for anyone managing a chronic condition.

This research represents the kind of scientific advancement that can genuinely improve outcomes for people with IBD. By understanding these connections earlier, we can catch problems sooner, when they’re more treatable. It’s a reminder that while living with IBD brings challenges, it also brings us into a community where researchers are constantly working to understand our condition better and improve our care.

The bottom line is this: you don’t need to be afraid, but you should be informed. This research gives you another tool in your advocacy toolkit—information you can share with your medical team to ensure you’re receiving comprehensive, holistic care that considers your IBD in the context of your overall health. In the world of chronic illness, knowledge really is power, and this kind of research gives us the power to be better advocates for our own health and well-being.

IBD Movement provides information for educational purposes only. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.