It’s Time to Stop Treating IBD Like It’s the Same Year-Round

Here’s a truth that might surprise your gastroenterologist: your IBD doesn’t read the calendar, but it absolutely responds to it. While we’ve made tremendous strides in understanding inflammatory bowel disease, we’re still treating it like a static condition that remains unchanged whether it’s sweltering July or frigid January. This one-size-fits-all approach is failing people with IBD, and it’s time we acknowledge that seasonal management isn’t just helpful—it’s essential.

The current medical paradigm treats IBD as if our bodies exist in a climate-controlled bubble, immune to the rhythms of nature and society. But anyone living with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis knows better. They feel the difference when the barometric pressure drops before a storm. They notice how their symptoms shift during the holidays or change with the seasons. Yet somehow, our treatment protocols haven’t caught up to this reality.

It’s time to revolutionize how we approach IBD care by embracing seasonal management strategies that work with our bodies’ natural responses to environmental and social changes, rather than pretending these factors don’t exist.

The Seasonal Reality We’re Ignoring

The evidence is mounting that IBD symptoms follow predictable seasonal patterns, yet most treatment plans remain frustratingly static. Research published in the Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis has shown that people with IBD experience more flares during certain times of year, with many reporting increased symptoms during fall and winter months. The reasons are multifaceted: decreased vitamin D levels, changes in gut microbiome composition, altered sleep patterns, and increased stress from holiday obligations.

Weather patterns play a particularly significant role that we’ve been slow to acknowledge. Barometric pressure changes can trigger inflammation in sensitive individuals. Cold weather often leads to dehydration—a major flare trigger that’s easily overlooked when we’re not sweating visibly. The dry indoor air of winter heating systems can affect our entire body’s inflammatory response.

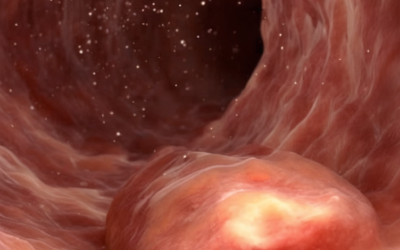

Then there’s the elephant in the room: the holidays. From Thanksgiving through New Year’s, people with IBD navigate a minefield of trigger foods, disrupted routines, family stress, and social pressure to “just eat normally for once.” We send them into this gauntlet with the same medication regimen they use in quiet February, then wonder why emergency department visits spike in December and January.

The current approach isn’t just inadequate—it’s setting people up for failure. We’re essentially telling someone to use summer tires year-round and then acting surprised when they slide off the road in a snowstorm.

A Proactive Framework for Seasonal IBD Management

What we need is a fundamental shift from reactive to proactive seasonal care. This means acknowledging that effective IBD management requires different strategies for different times of year, just like we wouldn’t use the same skincare routine in humid August and dry December.

Weather-responsive protocols should be standard practice. When we know a patient tends to flare during weather changes, we should be discussing preventive measures before storm season hits. This might include temporary increases in anti-inflammatory medications, enhanced hydration protocols, or stress management techniques for weather-sensitive individuals.

Consider vitamin D supplementation—a perfect example of how seasonal thinking could transform outcomes. We know that vitamin D deficiency correlates with increased IBD activity, and we know that levels naturally drop during winter months. Yet how many gastroenterologists proactively increase vitamin D supplementation in October rather than waiting for spring blood work to reveal deficiency? This reactive approach misses months of potential symptom prevention.

Holiday preparedness deserves its own category of care planning. October should trigger conversations about Thanksgiving meal planning, not December phone calls about emergency flares. We should be developing personalized holiday survival guides that include safe recipe modifications, strategies for navigating family food pressure, and temporary medication adjustments for travel.

The social aspect of seasonal challenges requires particular attention. Many people with IBD report that the stress of explaining their dietary restrictions repeatedly during holiday gatherings can be as triggering as the food itself. We need to equip patients with confidence-building strategies and practical scripts for these conversations.

Addressing the Skeptics

I anticipate pushback from those who argue that individualized seasonal protocols would be too complex to implement or that the evidence base isn’t strong enough to justify such an approach. These concerns deserve serious consideration.

The complexity argument has merit—seasonal management would require more nuanced care planning and closer patient-provider communication. However, complexity shouldn’t be an excuse for inadequacy. We already manage complex medication regimens and intricate dietary modifications. Adding seasonal considerations is an evolution, not a revolution, in care complexity.

As for evidence, critics might point out that large-scale studies on seasonal IBD management are limited. This is true, but it misses the point. We have substantial evidence that seasonal factors affect IBD symptoms, and we have evidence that various interventions can help manage these factors. The leap to seasonal protocols isn’t about proving something entirely new—it’s about applying what we already know in a more systematic way.

Some might argue that this approach could lead to over-medicalization or unnecessary anxiety about seasonal changes. This concern is valid but addressable through thoughtful implementation. Seasonal management shouldn’t create fear about certain times of year; rather, it should provide empowerment through preparation.

The most honest criticism is that seasonal protocols would require more time and resources from already-stretched healthcare providers. This is a real challenge that demands creative solutions, not dismissal of the approach entirely.

What Needs to Change Now

Healthcare providers need to start asking different questions during routine visits. Instead of just “How are your symptoms?” we should be asking “Have you noticed any patterns with weather changes?” and “What’s your biggest concern about the upcoming season?” These conversations should happen proactively—discussing winter management in fall appointments, not during emergency visits in February.

Medical education must evolve to include environmental and seasonal factors in IBD management training. Gastroenterology fellows should learn to think seasonally about treatment planning, just as they learn to think about drug interactions and surgical timing.

Patients themselves need to become active participants in tracking their seasonal patterns. This means keeping symptom diaries that include weather data, holiday stressors, and seasonal lifestyle changes. Many excellent apps can help with this tracking, but the key is consistent, long-term data collection that reveals individual patterns.

Insurance companies and healthcare systems need to recognize that preventive seasonal management could reduce costly emergency interventions. Covering nutritionist consultations before holiday seasons, or approving temporary medication adjustments based on historical patterns, could prevent expensive hospitalizations.

Research institutions should prioritize studies on seasonal IBD management protocols. We need data on optimal vitamin D supplementation timing, effectiveness of weather-based medication adjustments, and outcomes from proactive holiday management programs.

The Path Forward

Seasonal IBD management isn’t about making the condition more complicated—it’s about making care more effective by acknowledging reality. Our bodies don’t exist in isolation from the world around us, and our treatment shouldn’t pretend they do.

The shift toward seasonal thinking represents a broader evolution in chronic disease management, from one-size-fits-all protocols toward truly personalized care. People with IBD have been telling us for years that their symptoms change with the seasons, respond to weather patterns, and spike during holidays. It’s time we started listening systematically and responding proactively.

This isn’t about perfection—it’s about improvement. Even small steps toward seasonal awareness could prevent significant suffering. The patient who avoids a holiday flare because they planned ahead, or who maintains remission through winter because of proactive vitamin D management, represents success worth pursuing.

We have the knowledge and tools to do better. What we need now is the will to change how we think about IBD care—not as a battle against an unchanging enemy, but as a dynamic partnership with our bodies’ natural rhythms and responses. The seasons will keep changing whether we adapt our care or not. The question is whether we’ll finally start changing with them.