We Need to Stop Protecting Our Kids From Our IBD—And Start Preparing Them Instead

Here’s an uncomfortable truth that most IBD parents won’t admit: We’re failing our children by treating our condition like a family secret. Every time we whisper about our symptoms, rush to hide our medications, or pretend everything is fine during a flare-up, we’re teaching our kids that illness is shameful and that they can’t trust us to be honest about what affects our entire family.

It’s time for a fundamental shift in how we approach IBD parenting. Instead of shielding our children from our reality, we need age-appropriate transparency that prepares them for our unpredictable condition while preserving their childhood. This isn’t about burdening our kids—it’s about empowering them with knowledge, security, and the tools they need to thrive in a family where chronic illness is part of the landscape.

The Silence Is Hurting Everyone

Walk into any IBD support group, and you’ll hear the same stories repeated: children acting out when parents disappear for medical appointments without explanation, teens becoming anxious caregivers because they don’t understand boundaries, and families in crisis during flare-ups because no one prepared for the reality of chronic illness.

The current approach—what I call “protective silence”—stems from good intentions. We want to preserve our children’s innocence, avoid worrying them, and maintain some semblance of normalcy. But this strategy backfires spectacularly. Children are incredibly perceptive. When we hide our pain, cancel plans without explanation, or suddenly change our energy levels, they notice. Without accurate information, they fill in the gaps with their imagination, often creating scenarios far worse than reality.

Research consistently shows that children cope better with honest, age-appropriate information than with uncertainty and secrets. A 2019 study in the Journal of Pediatric Psychology found that children of parents with chronic illness who received clear explanations about their parent’s condition showed lower levels of anxiety and better behavioral adjustment than those kept in the dark.

Yet somehow, when it comes to IBD, we’ve convinced ourselves that our condition is too complex, too embarrassing, or too scary to discuss. We’re wrong on all counts.

Age-Appropriate Honesty Is the Answer

The solution isn’t complicated, but it requires us to abandon the myth that good parents protect their children from all difficult realities. Instead, we need to become skilled translators, converting our complex medical reality into language that makes sense at every developmental stage.

For toddlers and preschoolers (ages 2-5), the conversation should focus on basic concepts they can grasp. “Mommy’s tummy gets sick sometimes, and that’s why I need to rest or go to the doctor. It’s not your fault, and the doctors are helping me feel better.” At this age, consistency and reassurance matter more than medical details. What they need to understand is that illness happens, it’s being managed, and they are safe and loved.

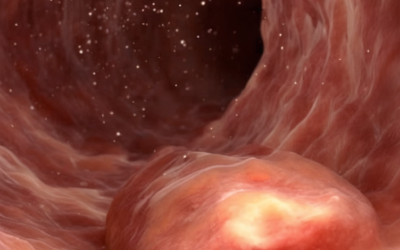

Elementary school children (ages 6-10) can handle more specifics without being overwhelmed. They can learn that IBD is a condition where the body’s immune system gets confused and attacks healthy parts of the digestive system. They can understand that certain foods might make symptoms worse, that medications help, and that flare-ups are temporary but unpredictable. Most importantly, they can learn practical information: who to call if you need help, what emergency plans look like, and how they can help without becoming responsible for your care.

Teenagers (ages 11+) deserve near-adult levels of honesty, delivered with appropriate emotional support. They can understand the autoimmune nature of IBD, the unpredictability of flares, the side effects of medications, and the long-term management strategies. They can also participate in family emergency planning and understand their role as informed family members, not caregivers.

The key is matching information to developmental capacity while maintaining consistent messaging: IBD is manageable, it’s not their fault or responsibility, and your family is prepared to handle whatever comes.

But What About the Counterarguments?

I anticipate pushback from parents who worry that honesty will traumatize their children or force them to grow up too fast. These concerns deserve serious consideration, but they often reflect our own discomfort with our diagnosis more than genuine child psychology.

Some parents argue that children shouldn’t have to worry about adult problems. I agree—which is exactly why we need to provide accurate information that reduces worry rather than letting their imaginations run wild. Others worry that discussing IBD will make children anxious about their own health or genetic risk. This concern has merit, but avoiding the conversation doesn’t eliminate the risk—it just ensures children won’t be prepared if symptoms do develop.

There’s also the argument that every family situation is different, and blanket recommendations don’t work. True, but this isn’t about one-size-fits-all scripts. It’s about establishing principles of age-appropriate honesty that each family can adapt to their circumstances, cultural background, and children’s individual needs.

Perhaps the strongest counterargument is that some children genuinely can’t handle certain information due to developmental delays, anxiety disorders, or other special circumstances. These families need individualized approaches, possibly with professional support. But these exceptions don’t negate the principle—they simply require more careful implementation.

What Needs to Change Right Now

First, IBD organizations and healthcare providers need to develop comprehensive resources for family communication. Currently, most patient education focuses on managing symptoms and medications, with family dynamics treated as an afterthought. We need age-specific communication guides, family emergency planning templates, and resources that help parents navigate difficult conversations.

Second, we need to normalize these discussions within the IBD community. Support groups should regularly address parenting challenges, and newly diagnosed parents should receive guidance on family communication as part of standard care. When we treat these conversations as optional extras rather than essential skills, we set families up for struggle.

Third, healthcare providers need training on family-centered care that includes children as stakeholders in their parent’s health journey. Pediatricians should be equipped to support children whose parents have chronic illnesses, and gastroenterologists should understand how IBD affects entire families, not just patients.

Finally, we need practical tools: scripts for common scenarios, emergency contact cards that children can understand, and family meeting templates that make these conversations feel manageable rather than overwhelming.

Most importantly, parents need to start having these conversations before crisis hits. The middle of a severe flare-up is not the time to explain IBD to your children for the first time. These discussions should happen during stable periods, when you can think clearly and your children can process information without the added stress of immediate crisis.

Building Stronger Families Through Honesty

When we embrace age-appropriate transparency about IBD, something remarkable happens: our children become more resilient, not more fragile. They learn that families can face challenges together, that medical conditions are manageable parts of life, and that honesty strengthens relationships rather than threatening them.

This doesn’t mean turning children into junior caregivers or overwhelming them with medical details. It means treating them as valued family members who deserve to understand the reality they’re living in and to feel prepared for the challenges that reality might bring.

Our children are already living with our IBD whether we acknowledge it or not. They’re already affected by our symptoms, our treatments, our good days and bad days. The only question is whether they’ll face these realities with accurate information and family support, or with confusion, secrecy, and unnecessary fear.

It’s time to choose transparency over protection, preparation over pretense. Our families—and our children’s futures—depend on it.